Why timing the market is a fool’s game.

Article written by Marek Krzeczkowski, Portfolio Manager and Henry Morrison-Jones, Investment Analyst at Mint Asset Management – 2nd May 2022

During bouts of market volatility, we often get questions from our clients about what changes we have made to our funds and whether it is a good idea for them to try and time the market. Despite how tempting it can be to sell during periods of uncertainty, making changes in the face of volatility is often counterproductive, especially given how much noise exists in the market. To help filter out this noise, it is essential to have a framework in place that can be used to look beyond current market conditions. Below, we look at some key things to remember when faced with market volatility and what that means in the context of our own investment framework.

As an old saying goes “In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not.” The plausibility of timing the market is a frequently broached topic in financial literature and almost always the conclusion is that it is nearly impossible to get right. What makes timing the market so tricky is that you must get it right twice – once on the way down and then again on the way up. Selling your holdings too late or buying them back too early often results in worse returns than if you had just held on throughout. After all, how can you be sure that the market has peaked or that the worst is over?

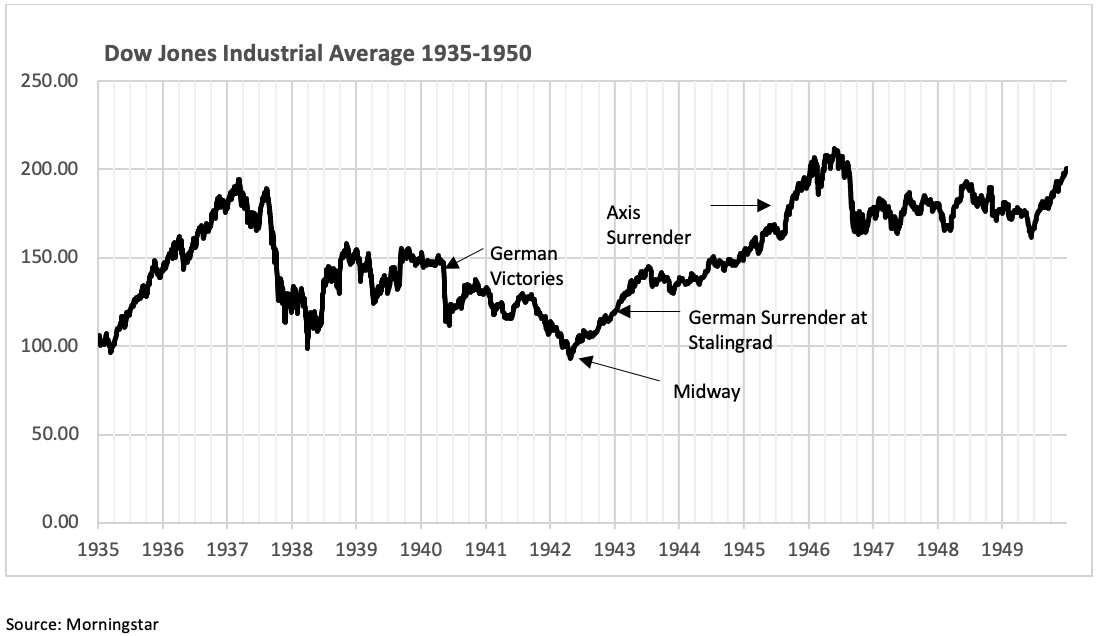

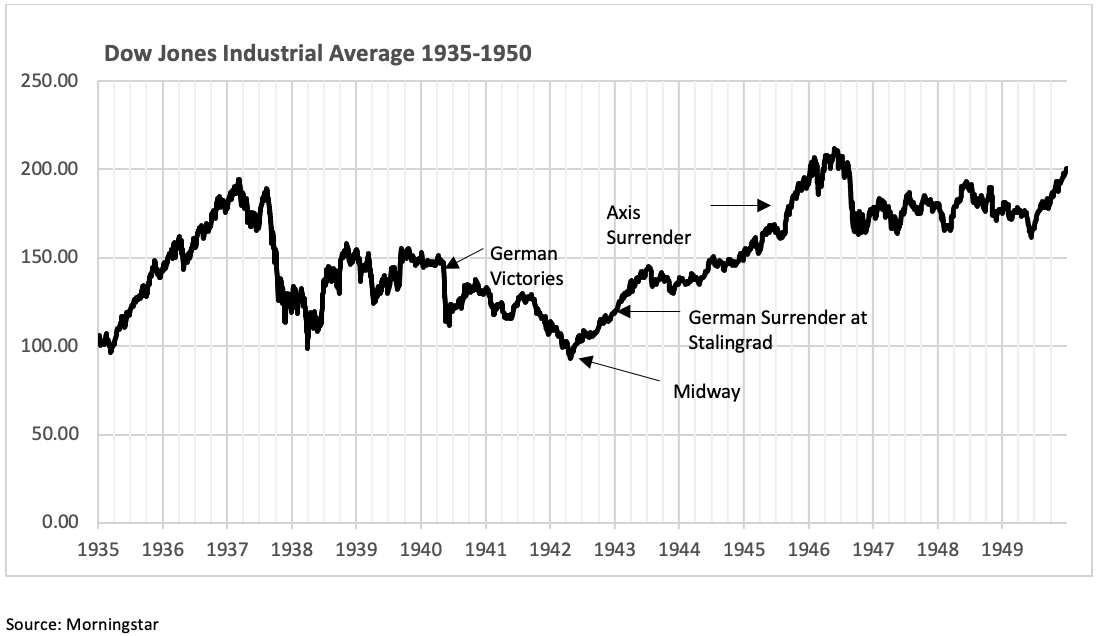

In hindsight, the relative peaks and troughs during market shocks appear obvious, but in the moment, what comes next can be incredibly hard to predict. A great example of how hard it can be to predict price floors and ceilings is to look at how markets reacted during the events of the Second World War.

Turning points are never obvious

Surprisingly, the absolute bottom during WWII was not the German surrender at Stalingrad, the news following D-Day, or the Axis surrender in 1945, but rather it was the Battle of Midway in June 1942. Ask any historian and they will tell you that even after the Battle of Midway, the war news was consistently bad. Timing is tricky as the markets tend to price in outcomes before they materialise. Often, even the news flow is a poor indicator of what comes next and while there were surely some who timed things right during the 1940s, it would have been an unlikely feat for most. History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes, and this example has some strong parallels to the events we are seeing today.

Even if you can interpret the significance of news and events better than most, there is so much news out there that it becomes difficult to know what is worth paying attention to in the first place. Separating news from noise has become increasingly difficult in the Information Age – an age where anyone who wants to be heard only needs to express their thoughts on Twitter in 280 characters or less. If you believe that following economic experts’ advice can help, finding the right expert can also be challenging. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that there are around 17,500 economists in the United States alone, all of whom are likely to have their own outlook on the economy shared through their reports, research, or medium of choice. Attempting to use every piece of information available to make investment decisions would leave even the most experienced investor completely lost.

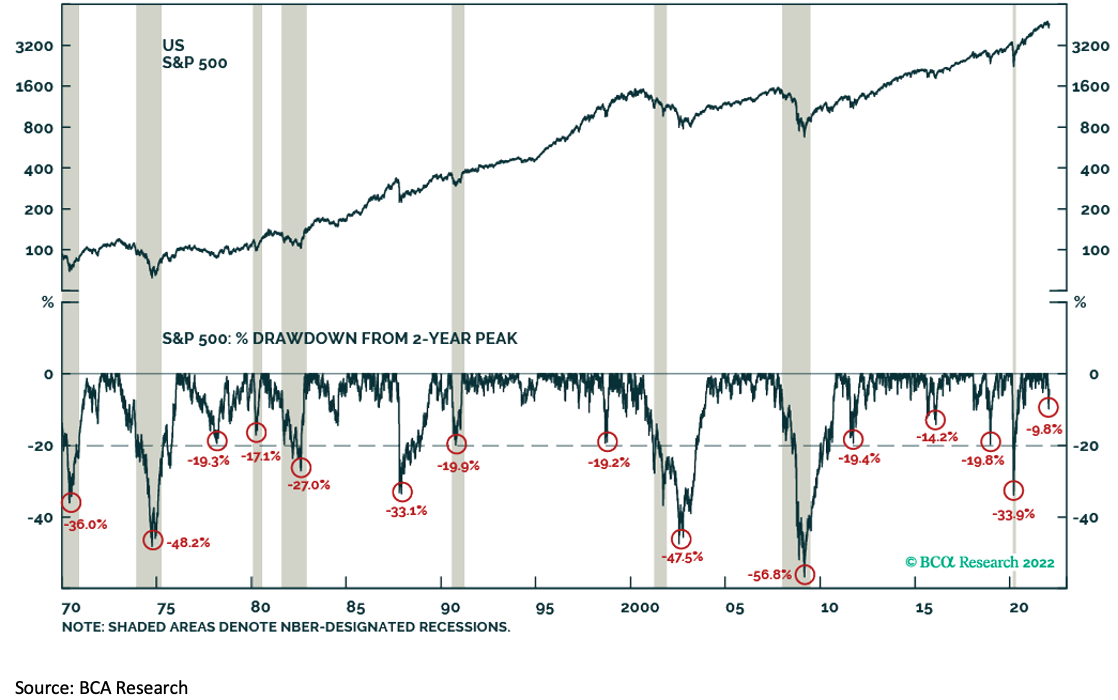

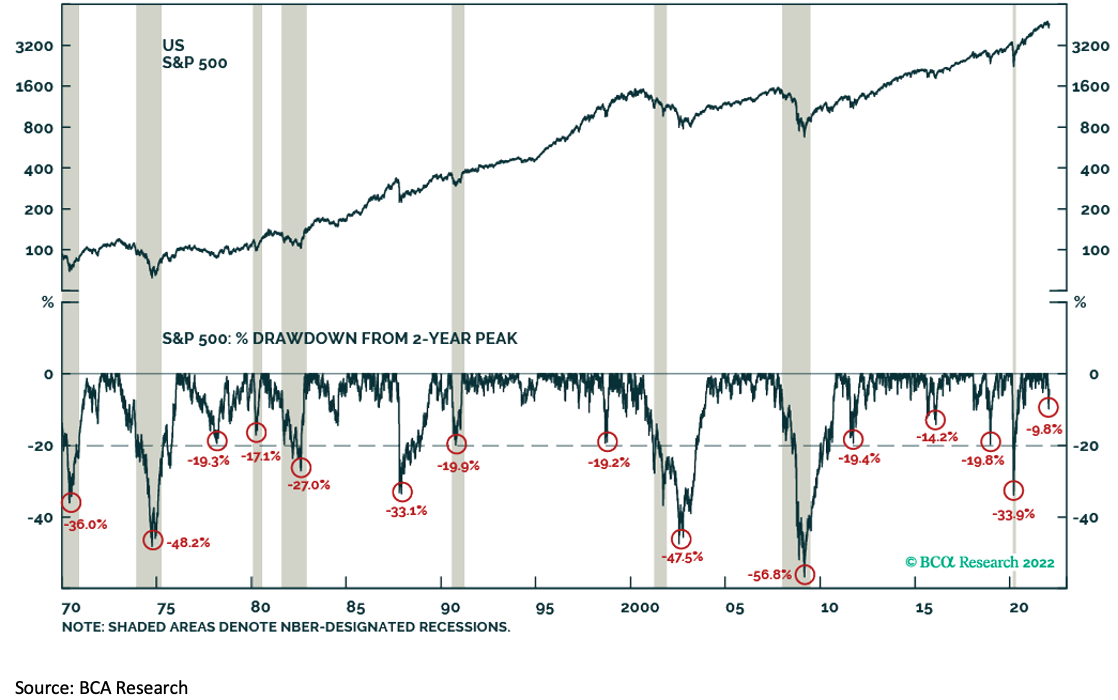

To filter out the noise, we evaluate new information in the context of a long-term investment horizon. In general, the less likely that a new piece of information is to change the long-term investment thesis, the less weight it carries in our decision-making process. Perhaps, the most obvious risk that can unhinge longer-term expectations is the risk of a recessionary crisis. Historically, stocks have peaked about six months before the onset of a recession, so usually, the best course of action is to stay invested if you expect the economy to continue tracking higher for at least the next 12 months. By focusing on what incoming data says about the probability of a recession, it becomes much easier to gauge the significance of new events and avoid short-term distractions.

It is the recessions that count

In a universe of tens of thousands of listed companies, it pays to know what you are looking for when picking stocks. Throughout our search, we focus on picking quality stocks with growth prospects; names that we believe will be winners for years to come. Trading in and out of companies that will outperform in the short-term increases turnover and the risk of getting things wrong. Similarly, just because the near-term environment is unfavourable for a high conviction long-term holding does not necessarily mean you should sell. One such example is our long-term holding of Amazon.com. Over the past twenty years, Amazon has disappointed on quarterly earnings twenty-four times, giving investors a reason to sell almost every year. And yet, this is a company with a cumulative 20-year return of more than 22,500%. Leaning too heavily into one of these earnings misses would have been costly for an investor with a short time horizon.

At Mint, the framework we use within our diversified funds helps us make better decisions for our clients. By focusing on the long-term, we are better positioned to filter short-term noise, reduce turnover and find quality businesses that can deliver sustained growth. As we publish this today, we acknowledge short term risks related to geopolitics and commodity prices but remain fully invested. This is because the probability of a global recession over the next 12 months remains low in our view. We see inflation pressures subsiding by the end of the year and central banks delivering fewer rate hikes than expected. Global growth will slow from recently elevated levels but should remain strong. Both equities and bonds should deliver positive returns over the next 12 months in this environment. Our investment framework is based primarily on our long-term view. Instead of trying to time the market, we focus our research on how to be best positioned to maximise long-term returns and on finding the best ideas to help us achieve that.

Disclaimer: Marek Krzeczkowski is the Portfolio Manager for the Diversified Growth and Diversified Income funds at Mint Asset Management. Henry Morrison-Jones is an Investment Analyst within the investment team at Mint Asset Management where he assists primarily with our Multi-Asset Funds. The above article is intended to provide information and does not purport to give investment advice. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Mint Asset Management is the issuer of the Mint Asset Management Funds. Download a copy of the product disclosure statement here.

Why timing the market is a fool’s game.

Article written by Marek Krzeczkowski, Portfolio Manager and Henry Morrison-Jones, Investment Analyst at Mint Asset Management – 2nd May 2022

During bouts of market volatility, we often get questions from our clients about what changes we have made to our funds and whether it is a good idea for them to try and time the market. Despite how tempting it can be to sell during periods of uncertainty, making changes in the face of volatility is often counterproductive, especially given how much noise exists in the market. To help filter out this noise, it is essential to have a framework in place that can be used to look beyond current market conditions. Below, we look at some key things to remember when faced with market volatility and what that means in the context of our own investment framework.

As an old saying goes “In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not.” The plausibility of timing the market is a frequently broached topic in financial literature and almost always the conclusion is that it is nearly impossible to get right. What makes timing the market so tricky is that you must get it right twice – once on the way down and then again on the way up. Selling your holdings too late or buying them back too early often results in worse returns than if you had just held on throughout. After all, how can you be sure that the market has peaked or that the worst is over?

In hindsight, the relative peaks and troughs during market shocks appear obvious, but in the moment, what comes next can be incredibly hard to predict. A great example of how hard it can be to predict price floors and ceilings is to look at how markets reacted during the events of the Second World War.

Turning points are never obvious

Surprisingly, the absolute bottom during WWII was not the German surrender at Stalingrad, the news following D-Day, or the Axis surrender in 1945, but rather it was the Battle of Midway in June 1942. Ask any historian and they will tell you that even after the Battle of Midway, the war news was consistently bad. Timing is tricky as the markets tend to price in outcomes before they materialise. Often, even the news flow is a poor indicator of what comes next and while there were surely some who timed things right during the 1940s, it would have been an unlikely feat for most. History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes, and this example has some strong parallels to the events we are seeing today.

Even if you can interpret the significance of news and events better than most, there is so much news out there that it becomes difficult to know what is worth paying attention to in the first place. Separating news from noise has become increasingly difficult in the Information Age – an age where anyone who wants to be heard only needs to express their thoughts on Twitter in 280 characters or less. If you believe that following economic experts’ advice can help, finding the right expert can also be challenging. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that there are around 17,500 economists in the United States alone, all of whom are likely to have their own outlook on the economy shared through their reports, research, or medium of choice. Attempting to use every piece of information available to make investment decisions would leave even the most experienced investor completely lost.

To filter out the noise, we evaluate new information in the context of a long-term investment horizon. In general, the less likely that a new piece of information is to change the long-term investment thesis, the less weight it carries in our decision-making process. Perhaps, the most obvious risk that can unhinge longer-term expectations is the risk of a recessionary crisis. Historically, stocks have peaked about six months before the onset of a recession, so usually, the best course of action is to stay invested if you expect the economy to continue tracking higher for at least the next 12 months. By focusing on what incoming data says about the probability of a recession, it becomes much easier to gauge the significance of new events and avoid short-term distractions.

It is the recessions that count

In a universe of tens of thousands of listed companies, it pays to know what you are looking for when picking stocks. Throughout our search, we focus on picking quality stocks with growth prospects; names that we believe will be winners for years to come. Trading in and out of companies that will outperform in the short-term increases turnover and the risk of getting things wrong. Similarly, just because the near-term environment is unfavourable for a high conviction long-term holding does not necessarily mean you should sell. One such example is our long-term holding of Amazon.com. Over the past twenty years, Amazon has disappointed on quarterly earnings twenty-four times, giving investors a reason to sell almost every year. And yet, this is a company with a cumulative 20-year return of more than 22,500%. Leaning too heavily into one of these earnings misses would have been costly for an investor with a short time horizon.

At Mint, the framework we use within our diversified funds helps us make better decisions for our clients. By focusing on the long-term, we are better positioned to filter short-term noise, reduce turnover and find quality businesses that can deliver sustained growth. As we publish this today, we acknowledge short term risks related to geopolitics and commodity prices but remain fully invested. This is because the probability of a global recession over the next 12 months remains low in our view. We see inflation pressures subsiding by the end of the year and central banks delivering fewer rate hikes than expected. Global growth will slow from recently elevated levels but should remain strong. Both equities and bonds should deliver positive returns over the next 12 months in this environment. Our investment framework is based primarily on our long-term view. Instead of trying to time the market, we focus our research on how to be best positioned to maximise long-term returns and on finding the best ideas to help us achieve that.

Disclaimer: Marek Krzeczkowski is the Portfolio Manager for the Diversified Growth and Diversified Income funds at Mint Asset Management. Henry Morrison-Jones is an Investment Analyst within the investment team at Mint Asset Management where he assists primarily with our Multi-Asset Funds. The above article is intended to provide information and does not purport to give investment advice. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Mint Asset Management is the issuer of the Mint Asset Management Funds. Download a copy of the product disclosure statement here.

Leave A Comment