Zero Minus Zero – Why Investors Are Looking For New Income Equations

Article written by InvestNow

June 2008 is a watershed nostalgia month for dewy-eyed NZ term deposit (TD) investors. With the global financial crisis (GFC) just three months away from its crescendo, care-free Kiwis were banking one-year term deposit returns of 8.5 per cent or thereabouts.

In that month the Reserve Bank of NZ (RBNZ) held the official cash rate (OCR) at the 21st century high of 8.25 per cent where it had risen to in September 2007.

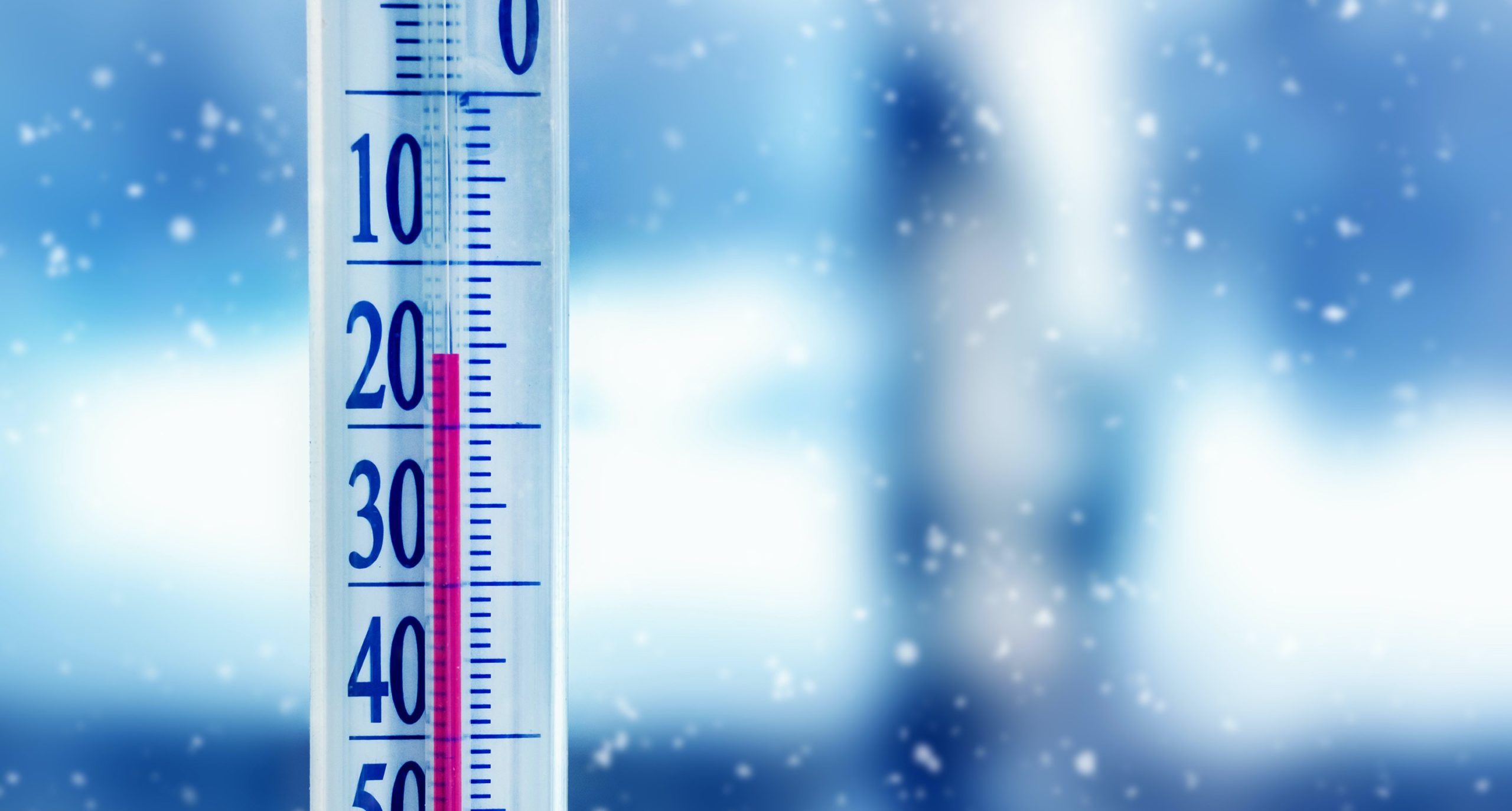

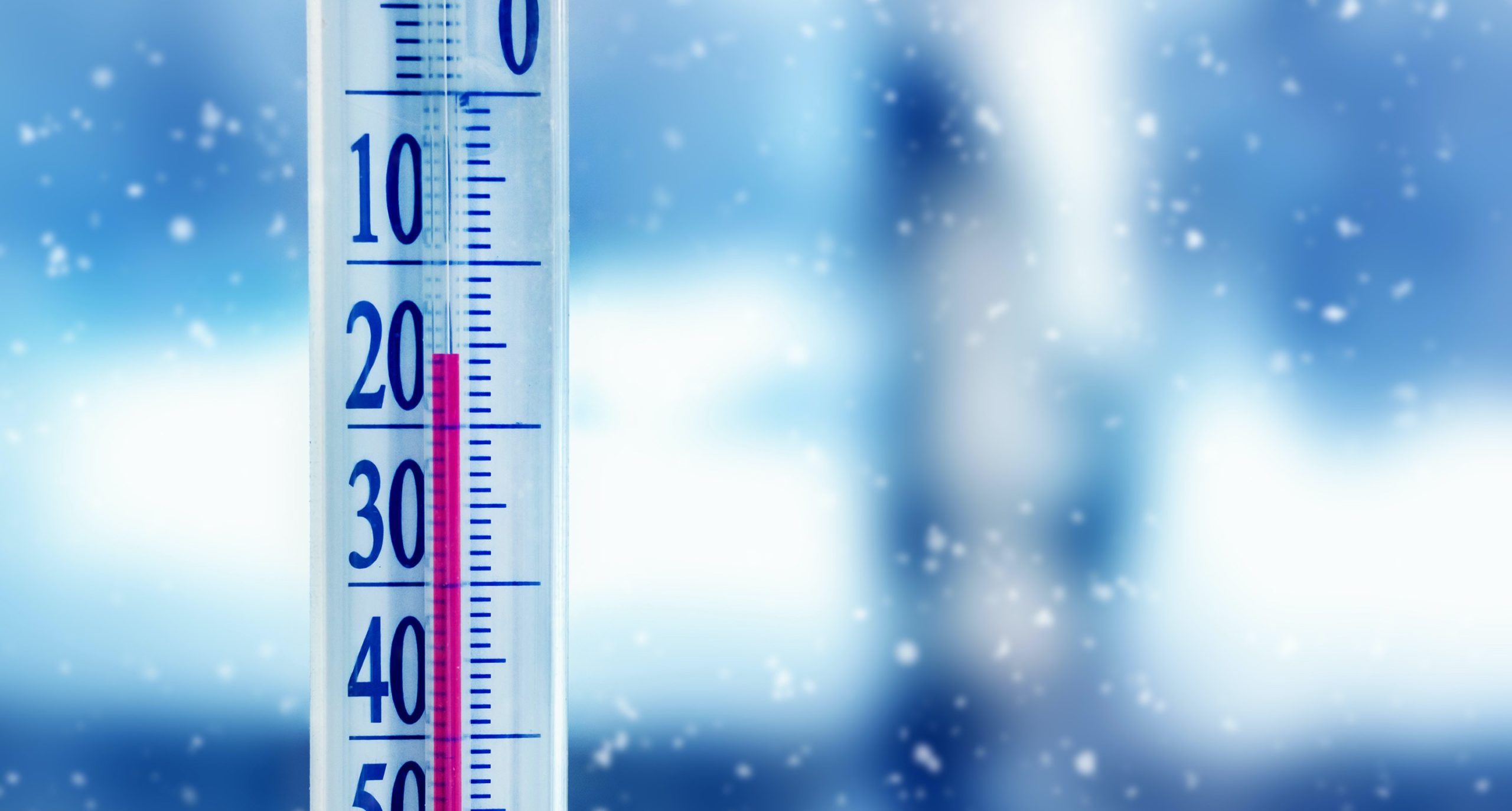

From June 2008 on, the OCR tracks mostly downwards, sinking to the current level of 0.25 per cent this March. But the OCR decline might not stop there: the RBNZ has flagged a potential trip beyond the ‘zero bound’, joining other jurisdictions in the negative-rates club.

Regardless of whether the OCR officially has a minus sign attached or not, the ultra-low interest rate era both in NZ and elsewhere poses big challenges for yield investors.

The return-free rate of risk

TDs, along with on-call cash accounts, are the simplest and most-popular regular income investments in NZ. Even today with interest rates plumbing all-time lows, Kiwis held just over $166 billion in TDs at the end of March. While that figure is down about $5 billion compared to February, total household bank deposits were higher month-on-month as lower lockdown spending saw cash account levels bubble up to $5 billion.

Note, too, that average TD returns – of which InvestNow offers an attractive suite – remain well above the OCR across a flat range of 2-3 per cent for all maturities. TDs are unlikely to fall below zero even if the OCR does, as banks will continue to compete for retail deposits to back lending.

However, the ‘real’, or after-inflation, rate of return for TDs is well below the 2008 heyday. In June 2008 the NZ inflation rate was about 5 per cent, implying real, ‘risk-free’ returns of circa 3.5 per cent for TD investors.

The latest official NZ consumers price index stands at 2.5 per cent (putting most TDs underwater relative to inflation). But the RBNZ is forecasting inflation to fall – perhaps even below zero – as the COVID-19 economic crisis plays out, presenting a different set of problems for fixed income investors.

Flat for the duration

Unlike TDs and cash-like products, bonds provide investors with dynamic exposure to interest rate movements. As TD investors have sucked up falling rates, bond managers, conversely, have enjoyed high returns since 2008. The mechanisms can be complex but, in short, the value of bonds issued at a certain yield is worth more than subsequent debt securities offering lower yields.

Bond managers can add or subtract this so-called ‘duration’ exposure to portfolios, depending on where they think interest rates are heading. If rates are forecast to head down (including sub-zero), managers look to add duration. On the other hand, if interest rates start to rise, bond investors exposed to long-duration assets stand to risk capital losses.

In periods of equity market stress, bonds have typically – but not always – provided a buffer against losses on shares. While the bond buffer loses some of its shine as rates approach zero, it’s worth noting that the top 15 best-performing funds on InvestNow during the March quarter – when global sharemarkets plunged – were fixed income or cash products.

Most retail investors, however, expect the fixed income asset class to stay true-to-label and deliver real income: a recurring series of cash payments to either spend or reinvest as they see fit. The problem today, as TD investors feel acute, is that yields on ‘risk-free’ fixed income assets have been flattened – and deliberately so – by central banks.

Central banks, including the RBNZ, are pulling out all the stops to lower the cost of lending to government and business to defibrillate moribund economies. In May, for instance, the RBNZ doubled its already record 2020 bond-buying program to $60 billion – about half of all NZ government debt.

The aim, as the RBNZ said in May, is to squash interest rates across all lending time-frames.

“As the return on lower-risk assets is reduced, the relative return on riskier assets becomes more attractive to investors,” the RBNZ statement says. “Investors are incentivised to rebalance their investments into riskier assets, thereby reducing the risk premiums of these assets as well. Overall, the level of all interest rates in the economy will fall.”

In other words, the central bank is actively encouraging investors to take on more risk with the unfortunate side-effect that returns on all asset classes will likely fall. Conservative yield-seeking investors, in particular, face some difficult choices.

Credit (and why it’s due)

Professional bond managers typically increase portfolio yields by taking on more ‘credit’ risk. In fixed income lingo, ‘credit’ refers to debt issued by companies while the vanilla ‘bond’ term generally denotes government debt. Given companies can go bankrupt more easily than countries, credit should provide investors with a higher return for the risk involved.

Since the GFC, though, the reward for allocating to credit relative to government debt shrunk as low rates and easy lending conditions prevailed. However, this March the ‘spreads’ between credit and government debt blew out as investors bet the COVID-19 emergency would see a rash of corporate debt defaults.

Credit spreads have since narrowed but remain higher than the pre-coronavirus levels, opening up yield opportunities (and also increasing risks) for savvy fixed-income investors. Many of the income-focused funds – including diversified products that also allocate to equities – on InvestNow can access both global and local credit markets.

The NZ corporate debt sector also now offers a potentially attractive alternative for income-seeking retail investors. More local companies are expected to release debt issues in the coming months to recapitalise post-COVID. And historically, NZ firms have extended debt offers direct to retail investors as well as institutions.

Corporate debt remains a much riskier asset class than TDs but that shouldn’t prevent self-directed investors who understand the trade-offs from including it in their portfolios. According to InvestNow general manager, Mike Heath, a recent survey found members would be interested in tapping into the local corporate bond market via the platform.

“We’re planning on adding NZ corporate bonds to InvestNow soon,” Heath says. “It will be a great complement to our other fixed income solutions that span diversified funds through to TDs.”

Zero Minus Zero – Why Investors Are Looking For New Income Equations

Article written by InvestNow

June 2008 is a watershed nostalgia month for dewy-eyed NZ term deposit (TD) investors. With the global financial crisis (GFC) just three months away from its crescendo, care-free Kiwis were banking one-year term deposit returns of 8.5 per cent or thereabouts.

In that month the Reserve Bank of NZ (RBNZ) held the official cash rate (OCR) at the 21st century high of 8.25 per cent where it had risen to in September 2007.

From June 2008 on, the OCR tracks mostly downwards, sinking to the current level of 0.25 per cent this March. But the OCR decline might not stop there: the RBNZ has flagged a potential trip beyond the ‘zero bound’, joining other jurisdictions in the negative-rates club.

Regardless of whether the OCR officially has a minus sign attached or not, the ultra-low interest rate era both in NZ and elsewhere poses big challenges for yield investors.

The return-free rate of risk

TDs, along with on-call cash accounts, are the simplest and most-popular regular income investments in NZ. Even today with interest rates plumbing all-time lows, Kiwis held just over $166 billion in TDs at the end of March. While that figure is down about $5 billion compared to February, total household bank deposits were higher month-on-month as lower lockdown spending saw cash account levels bubble up to $5 billion.

Note, too, that average TD returns – of which InvestNow offers an attractive suite – remain well above the OCR across a flat range of 2-3 per cent for all maturities. TDs are unlikely to fall below zero even if the OCR does, as banks will continue to compete for retail deposits to back lending.

However, the ‘real’, or after-inflation, rate of return for TDs is well below the 2008 heyday. In June 2008 the NZ inflation rate was about 5 per cent, implying real, ‘risk-free’ returns of circa 3.5 per cent for TD investors.

The latest official NZ consumers price index stands at 2.5 per cent (putting most TDs underwater relative to inflation). But the RBNZ is forecasting inflation to fall – perhaps even below zero – as the COVID-19 economic crisis plays out, presenting a different set of problems for fixed income investors.

Flat for the duration

Unlike TDs and cash-like products, bonds provide investors with dynamic exposure to interest rate movements. As TD investors have sucked up falling rates, bond managers, conversely, have enjoyed high returns since 2008. The mechanisms can be complex but, in short, the value of bonds issued at a certain yield is worth more than subsequent debt securities offering lower yields.

Bond managers can add or subtract this so-called ‘duration’ exposure to portfolios, depending on where they think interest rates are heading. If rates are forecast to head down (including sub-zero), managers look to add duration. On the other hand, if interest rates start to rise, bond investors exposed to long-duration assets stand to risk capital losses.

In periods of equity market stress, bonds have typically – but not always – provided a buffer against losses on shares. While the bond buffer loses some of its shine as rates approach zero, it’s worth noting that the top 15 best-performing funds on InvestNow during the March quarter – when global sharemarkets plunged – were fixed income or cash products.

Most retail investors, however, expect the fixed income asset class to stay true-to-label and deliver real income: a recurring series of cash payments to either spend or reinvest as they see fit. The problem today, as TD investors feel acute, is that yields on ‘risk-free’ fixed income assets have been flattened – and deliberately so – by central banks.

Central banks, including the RBNZ, are pulling out all the stops to lower the cost of lending to government and business to defibrillate moribund economies. In May, for instance, the RBNZ doubled its already record 2020 bond-buying program to $60 billion – about half of all NZ government debt.

The aim, as the RBNZ said in May, is to squash interest rates across all lending time-frames.

“As the return on lower-risk assets is reduced, the relative return on riskier assets becomes more attractive to investors,” the RBNZ statement says. “Investors are incentivised to rebalance their investments into riskier assets, thereby reducing the risk premiums of these assets as well. Overall, the level of all interest rates in the economy will fall.”

In other words, the central bank is actively encouraging investors to take on more risk with the unfortunate side-effect that returns on all asset classes will likely fall. Conservative yield-seeking investors, in particular, face some difficult choices.

Credit (and why it’s due)

Professional bond managers typically increase portfolio yields by taking on more ‘credit’ risk. In fixed income lingo, ‘credit’ refers to debt issued by companies while the vanilla ‘bond’ term generally denotes government debt. Given companies can go bankrupt more easily than countries, credit should provide investors with a higher return for the risk involved.

Since the GFC, though, the reward for allocating to credit relative to government debt shrunk as low rates and easy lending conditions prevailed. However, this March the ‘spreads’ between credit and government debt blew out as investors bet the COVID-19 emergency would see a rash of corporate debt defaults.

Credit spreads have since narrowed but remain higher than the pre-coronavirus levels, opening up yield opportunities (and also increasing risks) for savvy fixed-income investors. Many of the income-focused funds – including diversified products that also allocate to equities – on InvestNow can access both global and local credit markets.

The NZ corporate debt sector also now offers a potentially attractive alternative for income-seeking retail investors. More local companies are expected to release debt issues in the coming months to recapitalise post-COVID. And historically, NZ firms have extended debt offers direct to retail investors as well as institutions.

Corporate debt remains a much riskier asset class than TDs but that shouldn’t prevent self-directed investors who understand the trade-offs from including it in their portfolios. According to InvestNow general manager, Mike Heath, a recent survey found members would be interested in tapping into the local corporate bond market via the platform.

“We’re planning on adding NZ corporate bonds to InvestNow soon,” Heath says. “It will be a great complement to our other fixed income solutions that span diversified funds through to TDs.”