The investment wow factor: why tax matters

Article written by Anthony Edmonds, Founder and Managing Director of InvestNow – 5th October 2022

It was the briefcases.

Watching dancers twirling the old-fashioned hard-case executive handbags at the recent World of WearableArts (WOW) show in Wellington transported me to glamorous memories of… tax.

Everyone had briefcases then, including the sharebroker (now rebranded as a ‘wealth adviser’) who was explaining how his company – which managed many billions of dollars on behalf of tens of thousands of Kiwis – incorporated tax into its investment decision-making process.

“We don’t,” he said. “It’s all a bit complicated and, really, what does it matter?”

Wow.

Tax makes a big difference to long-term investment returns even if it was in the short-term interests of the sharebroker-cum-wealth-adviser to dance around that fact.

Brokers, of course, are rewarded for encouraging clients to trade individual shares and bonds rather than create tax-optimised portfolios.

But stripping down investment to its core purpose reveals why tax is intrinsic to the process.

At its heart, investment is about accumulating enough assets to pay for any future liabilities such as ensuring a comfortable retirement.

While everyone will have different individual ‘liabilities’, those future expenses must be paid by after-tax investment returns (or dipping into capital).

Cleary, investors have a better chance of achieving their long-term spending goals by minimising the impact of tax – regardless of what any sharebroker-cum-wealth-adviser might say.

People need to meet annual expenditure out of tax-paid earnings, which is reflected by the fact that every wage-earner intuitively understands the need to account for tax when balancing wage income with spending requirements; investors should do likewise.

Professional investors certainly consider tax when assembling portfolios, which is easily demonstrated by the long-term asset allocation differences between KiwiSaver schemes and charitable funds.

As NZ tax-paying entities, KiwiSaver funds benefit from access to ‘imputation credits’ – effectively, a rebate to recognise tax already paid by underlying firms – of local companies.

Consequently, KiwiSaver schemes (and the like) tend to have a higher allocation to NZ shares compared to charitable funds, which do not have to pay tax here and can’t benefit from the imputation credits.

The average KiwiSaver balanced fund, for example, has about 35% in global equities and 15% in local shares; by contrast, the Otago Community Trust has a similar exposure to international stocks but only 7% in local equities.

Professional investors consider the impact of tax both at the asset allocation level – as per the NZ shares example above – and in the vehicles they use to access those underlying assets.

Most institutional-grade KiwiSaver and other investment providers, for example, choose to hold the majority of their assets (typically, shares and bonds) in tax-efficient locally domiciled portfolio investment entity (PIE) funds: the InvestNow KiwiSaver Scheme is built to such institutional specifications for that reason.

At InvestNow one of our core tenets is empowering everyday investors with the tools and knowledge to create portfolios to high professional standards.

In addition to making sure that portfolios should match individual objectives, time horizon, and risk preferences we believe investors also need to consider the total costs of investing, taking into account both fees and taxes.

And while the NZ investment tax regime features some interesting quirks (including different treatments for Australasian shares, global shares and fixed income assets), PIEs generally offer many advantages over other fund structures or directly held securities across equities and fixed income assets.

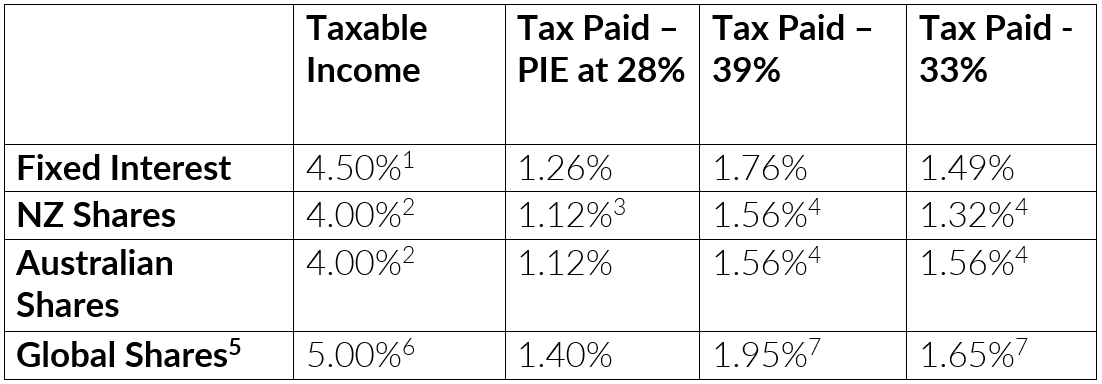

As the table below shows, PIEs, which have a top tax rate of just 28%, can provide a substantial benefit over other methods where investors face a tax on returns at their marginal rates. All investors on a marginal rate of 30% or more (especially the top tiers of 33% and 39%) can reap better after-tax returns via PIEs. The table shows the amount of tax that investors pay in PIE funds, versus being taxed if they held assets directly and are taxed at their higher personal tax rate:

- The whole fixed interest return is subject to tax, reflecting these assets are taxed on an accruals basis.

- For NZ and Australian shares, only the underlying company dividends are subject to tax provided these companies aren’t Australian property funds or listed Australian investment funds (which are taxed like global shares).

- The NZ share PIE fund’s tax liability will be further reduced as a result of getting a deduction for any management fees, plus a benefit/credit for the imputation credits. This will mean that the actual tax liability is closer to zero. PIEs are explicitly exempt from tax on capital gains.

- For directly held NZ and Australian shares the IRD could deem an investor to be a trader, meaning they have to pay capital gains tax. Also note that brokerage fees are not typically tax deductible.

- In this line we have assumed the PIE holds the underlying global shares directly.

- Under Fair Dividend Regime (FDR), the annual taxable income is deemed to be 5%.

- Assumes the investor has more than $50,000 invested in offshore shares, and being taxed under FDR. Individuals can switch between FDR and Comparative Value (CV) for their directly held global shares provided they use one methodology for all their global shares.

In spite of the compelling evidence in favour of PIEs, many broker-linked wealth advisers still encourage clients to invest in directly held portfolios of shares and fixed income. The difference is particularly stark when looking at the standard sharebroker-type allocation to the latter asset class.

Tax is a major cost that eats into investors’ returns: it matters. Anyone claiming that investors can ignore tax either demonstrates a lack to knowledge or a vested profit-based interest.

Importantly, platforms or broker-based advisers promoting investing directly in shares and fixed interest securities have no legal obligations to explain the short-comings of this approach.

As shown in the earlier table, for investors on higher tax rates (33% and 39%), PIE funds provide ‘no brainer’ compelling tax benefits within the fixed interest and Australasian equity sectors.

While tax for global shares can be needlessly complicated for NZ investors (we will explain this in future articles), well-structured PIE funds in this sector also provide meaningful benefits.

Global equity PIE funds offer particular advantages over poorly structured direct portfolios or funds that don’t account for factors such as tax slippage.

Investors need to question the motives of anybody promoting the virtues of managing a portfolio of directly held securities considering the tax and other practical complications involved – complexities that are rarely, if ever, explained in the sales pitch.

Broker-designed portfolios tend to exclude global bonds, for example, while holding, say, 20 or 30 local fixed income instruments in an asset allocation decision that would horrify institutional investors.

Given the decent choice of broadly diversified global and NZ fixed income tax-advantaged PIEs available to investors here, the broker preference for a smattering of local-only bonds is curious: perhaps the ability to pocket trading fees explains it (and maybe that was what the briefcase was for).

Meanwhile, investors – especially those on high marginal rates – left holding the bag of direct shares and bonds after the salesman pirouettes out the door might wonder why anyone would advise them to pay more tax than necessary.

The investment wow factor: why tax matters

Article written by Anthony Edmonds, Founder and Managing Director of InvestNow – 5th October 2022

It was the briefcases.

Watching dancers twirling the old-fashioned hard-case executive handbags at the recent World of WearableArts (WOW) show in Wellington transported me to glamorous memories of… tax.

Everyone had briefcases then, including the sharebroker (now rebranded as a ‘wealth adviser’) who was explaining how his company – which managed many billions of dollars on behalf of tens of thousands of Kiwis – incorporated tax into its investment decision-making process.

“We don’t,” he said. “It’s all a bit complicated and, really, what does it matter?”

Wow.

Tax makes a big difference to long-term investment returns even if it was in the short-term interests of the sharebroker-cum-wealth-adviser to dance around that fact.

Brokers, of course, are rewarded for encouraging clients to trade individual shares and bonds rather than create tax-optimised portfolios.

But stripping down investment to its core purpose reveals why tax is intrinsic to the process.

At its heart, investment is about accumulating enough assets to pay for any future liabilities such as ensuring a comfortable retirement.

While everyone will have different individual ‘liabilities’, those future expenses must be paid by after-tax investment returns (or dipping into capital).

Cleary, investors have a better chance of achieving their long-term spending goals by minimising the impact of tax – regardless of what any sharebroker-cum-wealth-adviser might say.

People need to meet annual expenditure out of tax-paid earnings, which is reflected by the fact that every wage-earner intuitively understands the need to account for tax when balancing wage income with spending requirements; investors should do likewise.

Professional investors certainly consider tax when assembling portfolios, which is easily demonstrated by the long-term asset allocation differences between KiwiSaver schemes and charitable funds.

As NZ tax-paying entities, KiwiSaver funds benefit from access to ‘imputation credits’ – effectively, a rebate to recognise tax already paid by underlying firms – of local companies.

Consequently, KiwiSaver schemes (and the like) tend to have a higher allocation to NZ shares compared to charitable funds, which do not have to pay tax here and can’t benefit from the imputation credits.

The average KiwiSaver balanced fund, for example, has about 35% in global equities and 15% in local shares; by contrast, the Otago Community Trust has a similar exposure to international stocks but only 7% in local equities.

Professional investors consider the impact of tax both at the asset allocation level – as per the NZ shares example above – and in the vehicles they use to access those underlying assets.

Most institutional-grade KiwiSaver and other investment providers, for example, choose to hold the majority of their assets (typically, shares and bonds) in tax-efficient locally domiciled portfolio investment entity (PIE) funds: the InvestNow KiwiSaver Scheme is built to such institutional specifications for that reason.

At InvestNow one of our core tenets is empowering everyday investors with the tools and knowledge to create portfolios to high professional standards.

In addition to making sure that portfolios should match individual objectives, time horizon, and risk preferences we believe investors also need to consider the total costs of investing, taking into account both fees and taxes.

And while the NZ investment tax regime features some interesting quirks (including different treatments for Australasian shares, global shares and fixed income assets), PIEs generally offer many advantages over other fund structures or directly held securities across equities and fixed income assets.

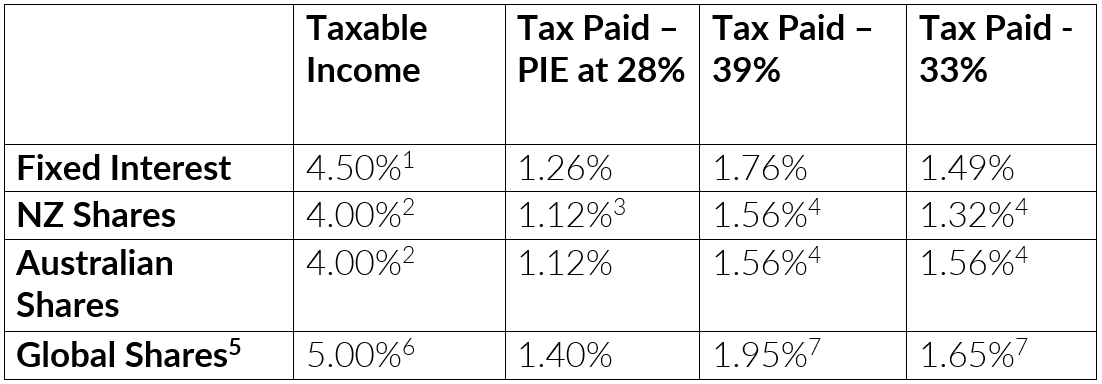

As the table below shows, PIEs, which have a top tax rate of just 28%, can provide a substantial benefit over other methods where investors face a tax on returns at their marginal rates. All investors on a marginal rate of 30% or more (especially the top tiers of 33% and 39%) can reap better after-tax returns via PIEs. The table shows the amount of tax that investors pay in PIE funds, versus being taxed if they held assets directly and are taxed at their higher personal tax rate:

- The whole fixed interest return is subject to tax, reflecting these assets are taxed on an accruals basis.

- For NZ and Australian shares, only the underlying company dividends are subject to tax provided these companies aren’t Australian property funds or listed Australian investment funds (which are taxed like global shares).

- The NZ share PIE fund’s tax liability will be further reduced as a result of getting a deduction for any management fees, plus a benefit/credit for the imputation credits. This will mean that the actual tax liability is closer to zero. PIEs are explicitly exempt from tax on capital gains.

- For directly held NZ and Australian shares the IRD could deem an investor to be a trader, meaning they have to pay capital gains tax. Also note that brokerage fees are not typically tax deductible.

- In this line we have assumed the PIE holds the underlying global shares directly.

- Under Fair Dividend Regime (FDR), the annual taxable income is deemed to be 5%.

- Assumes the investor has more than $50,000 invested in offshore shares, and being taxed under FDR. Individuals can switch between FDR and Comparative Value (CV) for their directly held global shares provided they use one methodology for all their global shares.

In spite of the compelling evidence in favour of PIEs, many broker-linked wealth advisers still encourage clients to invest in directly held portfolios of shares and fixed income. The difference is particularly stark when looking at the standard sharebroker-type allocation to the latter asset class.

Tax is a major cost that eats into investors’ returns: it matters. Anyone claiming that investors can ignore tax either demonstrates a lack to knowledge or a vested profit-based interest.

Importantly, platforms or broker-based advisers promoting investing directly in shares and fixed interest securities have no legal obligations to explain the short-comings of this approach.

As shown in the earlier table, for investors on higher tax rates (33% and 39%), PIE funds provide ‘no brainer’ compelling tax benefits within the fixed interest and Australasian equity sectors.

While tax for global shares can be needlessly complicated for NZ investors (we will explain this in future articles), well-structured PIE funds in this sector also provide meaningful benefits.

Global equity PIE funds offer particular advantages over poorly structured direct portfolios or funds that don’t account for factors such as tax slippage.

Investors need to question the motives of anybody promoting the virtues of managing a portfolio of directly held securities considering the tax and other practical complications involved – complexities that are rarely, if ever, explained in the sales pitch.

Broker-designed portfolios tend to exclude global bonds, for example, while holding, say, 20 or 30 local fixed income instruments in an asset allocation decision that would horrify institutional investors.

Given the decent choice of broadly diversified global and NZ fixed income tax-advantaged PIEs available to investors here, the broker preference for a smattering of local-only bonds is curious: perhaps the ability to pocket trading fees explains it (and maybe that was what the briefcase was for).

Meanwhile, investors – especially those on high marginal rates – left holding the bag of direct shares and bonds after the salesman pirouettes out the door might wonder why anyone would advise them to pay more tax than necessary.

Sage advice from a master