InvestNow News – 5th February – Harbour Asset Management – When will central banks react to inflation?

Article written by Hamish Pepper, Harbour Asset Management – 29th January 2021

- Higher inflation and the prospect of a reduction in central bank support is becoming a concern among financial market participants.

- We think this risk is low given most economies have spare capacity that is keeping unemployment rates higher and inflation lower than central banks desire.

- The ongoing threat of higher inflation and reduced monetary stimulus, however, is likely to lead to choppy trading conditions as investors manage the transition away from the low inflation and falling interest rate environment seen in recent years.

- We hope that the following Q&A gives you an insight into our thought process.

Higher inflation and the prospect of a reduction in central bank support is becoming a concern among financial market participants. Some are even worrying about a repeat of the 2013 “taper tantrum” when 10-year US Treasury yields increased more than 1 percentage point after the US Federal Reserve indicated its intention to reduce the pace of asset purchases if the economy continued to improve. Some market participants also recall the more substantive 2 percentage point rise in those bond yields in 1994 when inflation surprised to the upside.

We think this risk is low given most economies have spare capacity that is keeping unemployment rates higher and inflation lower than central banks desire. Even in the case where central bank objectives are met, their new “average inflation targeting” approach means they will likely want to see several quarters of this environment before moving policy to less accommodative settings.

The ongoing threat of higher inflation and reduced monetary stimulus, however, is likely to keep financial market participants on their toes. In New Zealand, this concern was recently fueled by higher-than-expected Q4 CPI inflation that showed some evidence of less discounting in retail sectors and more significant price rises in the construction sector. We expect choppy trading conditions as investors manage the transition away from the low inflation and falling interest rate environment seen in recent years.

We hope that the following Q&A gives you an insight into our thought process.

What are central banks doing right now?

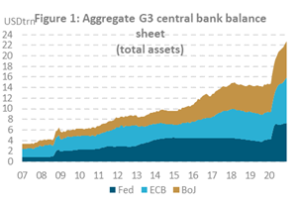

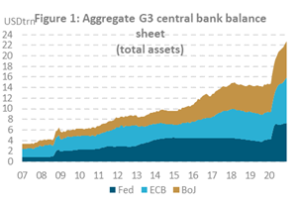

Central banks continue to provide stimulus by buying large amounts of fixed income assets (mostly government bonds) under quantitative easing (QE) programmes to keep interest rates low and yield curves flatter than they otherwise would be. QE was initiated early last year after cutting policy rates close to their effective lower bounds. The Fed, for example, bought more than US$3trn of bonds in 2020 (14% of GDP) and is currently buying $120bn of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities per month (see Figure 1). In New Zealand, the RBNZ has bought $45bn of bonds (15% of GDP) within its $100bn Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) programme and is currently buying $2.6bn of government bonds per month.

But economies have recovered strongly, why is so much monetary stimulus still being provided?

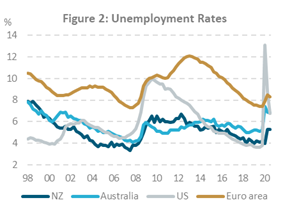

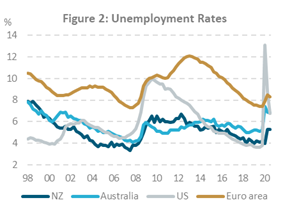

Economic growth has indeed been impressive in recent quarters but the level of economic activity in most countries suggests spare capacity remains and this is keeping inflation below central bank targets. This is most obvious in labour markets, where developed economy unemployment rates are above those consistent with full employment – a specific objective for many central banks, in addition to inflation (see Figure 2). While central banks, like most analysts, have underestimated the strength of the recovery, they are not willing to recalibrate policy settings yet, as they fear that any move to remove stimulus could trigger stress and volatility in markets, undermining much of the progress that has been made.

Money growth has gone moon-bound, surely inflation is a foregone conclusion?

Large QE programmes have indeed resulted in huge increases in money supply but, outside the housing sector, demand for this money remains relatively weak (see Figure 3). The quantity theory of money states that prices are a function of money times its velocity (the rate at which money is exchanged in the economy), divided by real output. While money has increased, the velocity of that money remains low so that prices of goods and services have not changed materially. The velocity of money is likely to pick up as economies continue to recover.

Aren’t central banks forward looking?

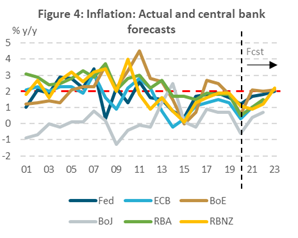

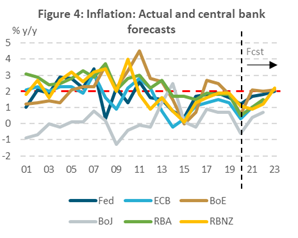

Central banks seem much less forward looking these days. After a decade of missing inflation targets to the downside, many central banks have adopted an average inflation targeting approach since COVID; the US Federal Reserve most formally (see Figure 4). Within this new framework, central banks are placing much greater emphasis on actual outcomes rather than forecast outcomes, i.e. they want to see inflation above 2% and full employment for several quarters before contemplating less accommodative policy settings. Most economists do not forecast these conditions to be met in the next 2-3 years.

What are financial markets saying about inflation?

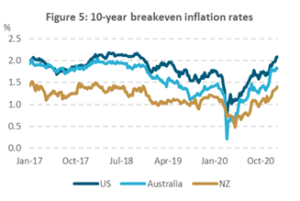

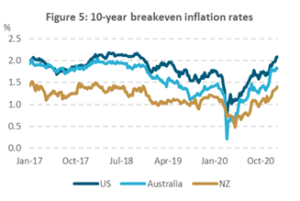

Markets are becoming more aware of inflation risks. This is due not only to the surprisingly strong economic recovery but also the perceived risk that the approach of central banks may prove to be too slow if inflation does accelerate. Corporates are regularly beating revenue expectations and, in some sectors, noting pricing pressures. Breakeven inflation rates (the difference between nominal bond yields and those of inflation-linked/protected securities) have risen sharply. 10-year inflation breakeven rates are above 2% in the US, close to 2% in Australia and around 1.4% in NZ (see Figure 5). Strong performance in real assets, e.g. property, also speaks to growing concerns about inflation risks.

Do surveys concur?

The evidence is mixed (see Figure 6). The US Philadelphia Fed’s survey of professional forecasters shows their expectations of 10-year ahead US inflation increased slightly at the end of 2020 but remains below 2%. Similarly, the RBNZ’s survey showed 2-year ahead expectations are 1.6%, versus 1.2% in the June 2020 quarter. In contrast, the US ISM survey of manufacturing firms shows prices paid for inputs are increasing – perhaps reflecting supply chain disruptions that some economists assume will be transitory.

How should I think about inflation?

Inflation will mean different things to different people. Some people are mostly concerned about their weekly grocery bills, others about the increasing costs of healthcare and housing. Rapidly increasing inflation impacts the efficiency of an economy; and is more often associated with higher interest rates, lower investment and lower employment.

In a technical sense, most central banks and economists work within a New Keynesian Phillips Curve framework[1] where inflation is a function of the output gap (ie, the level of economic output versus potential, a measure of capacity pressure), historical realised inflation to capture inflation inertia and inflation expectations. For open economies, supply-side variables are often added including changes in oil prices, changes in world manufactured export prices and changes in the nominal effective exchange rate.

What is the risk and how might markets respond?

The most serious risk to asset markets generally is materially higher and persistent inflation. This could happen if spare economic capacity is being overestimated or is reduced more quickly than anticipated. It is likely, for example, that potential GDP growth in New Zealand has slowed due to border closure and the drop in immigration – reducing the growth rate in labour supply.

This unexpected inflation pressure could be exacerbated if COVID-related supply disruptions also persist. The market reaction to this will be determined by whether central banks choose option a) or b):

a) If central banks remain “behind the curve” and leave policy settings unchanged, bond yields are likely to rise substantially (reducing the value of these assets) as they price higher future inflation and economic growth. Inflation-protected securities are likely to benefit.

Equity markets may initially be encouraged by the continuation of central bank support, however at some point equity markets may also react negatively to higher inflation, higher bond yields and the risk of a more sudden rise in interest rates. Historically, inflation averaging between 1-4% has been a better zone for equity market performance.

b) If, instead, central banks show concern about the higher inflation, markets are likely to bring forward expectations of rate hikes and a cessation of QE. Bond yields will likely rise, but by a smaller amount, and inflation-protected securities will not benefit to the same degree.

Equity markets may experience a mixed performance in this scenario with the prospect of cyclicals outperforming utilities, property, and long-dated growth stocks. Given current elevated equity valuations a more prolonged rise in inflation could have a more negative implication for both fixed interest and equity markets.

Sources: Bloomberg, Reserve Bank of New Zealand, US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, Reserve Bank of Australia.

[1] New Zealander William (Bill) Phillips formalised the relationship between inflation and capacity pressure in the 1950’s by documenting (by hand!) the negative statistical relationship observed between UK wage inflation and unemployment. The “Phillips Curve” was quickly adopted by Keynesian economists that believed monetary and fiscal policy can help stabilise economic output over the business cycle, i.e. economic output does not always equal the potential amount of output. This original specification, however, fell victim to critique by the famous monetarist, Milton Friedman, who argued that any efforts to increase output beyond its “natural” level would be constrained by rising real wages as workers adjusted their inflation expectations. The “New Keynesian” response was to incorporate rational expectations (an inflation expectation term) and allow a role for monetary policy by assuming, based on microeconomic justification (menu costs, for example), that prices are sticky.

IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER

Harbour Asset Management Limited is the issuer and manager of the Harbour Investment Funds. Investors must receive and should read carefully the Product Disclosure Statement, available at www.harbourasset.co.nz. We are required to publish quarterly Fund updates showing returns and total fees during the previous year, also available at www.harbourasset.co.nz. Harbour Asset Management Limited also manages wholesale unit trusts. To invest as a Wholesale Investor, investors must fit the criteria as set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013. This publication is provided in good faith for general information purposes only. Information has been prepared from sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of publication, but this is not guaranteed. Information, analysis or views contained herein reflect a judgement at the date of publication and are subject to change without notice. This is not intended to constitute advice to any person. To the extent that any such information, analysis, opinions or views constitutes advice, it does not consider any person’s particular financial situation or goals and, accordingly, does not constitute personalised advice under the Financial Advisers Act 2008. This does not constitute advice of a legal, accounting, tax or other nature to any persons. You should consult your tax adviser in order to understand the impact of investment decisions on your tax position. The price, value and income derived from investments may fluctuate and investors may get back less than originally invested. Where an investment is denominated in a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may have an adverse effect on the value, price or income of the investment. Actual performance will be affected by fund charges as well as the timing of an investor’s cash flows into or out of the Fund. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance. Neither Harbour Asset Management Limited nor any other person guarantees repayment of any capital or any returns on capital invested in the investments. To the maximum extent permitted by law, no liability or responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage, direct or consequential, arising from or in connection with this or its contents.

InvestNow News – 5th February – Harbour Asset Management – When will central banks react to inflation?

Article written by Hamish Pepper, Harbour Asset Management – 29th January 2021

- Higher inflation and the prospect of a reduction in central bank support is becoming a concern among financial market participants.

- We think this risk is low given most economies have spare capacity that is keeping unemployment rates higher and inflation lower than central banks desire.

- The ongoing threat of higher inflation and reduced monetary stimulus, however, is likely to lead to choppy trading conditions as investors manage the transition away from the low inflation and falling interest rate environment seen in recent years.

- We hope that the following Q&A gives you an insight into our thought process.

Higher inflation and the prospect of a reduction in central bank support is becoming a concern among financial market participants. Some are even worrying about a repeat of the 2013 “taper tantrum” when 10-year US Treasury yields increased more than 1 percentage point after the US Federal Reserve indicated its intention to reduce the pace of asset purchases if the economy continued to improve. Some market participants also recall the more substantive 2 percentage point rise in those bond yields in 1994 when inflation surprised to the upside.

We think this risk is low given most economies have spare capacity that is keeping unemployment rates higher and inflation lower than central banks desire. Even in the case where central bank objectives are met, their new “average inflation targeting” approach means they will likely want to see several quarters of this environment before moving policy to less accommodative settings.

The ongoing threat of higher inflation and reduced monetary stimulus, however, is likely to keep financial market participants on their toes. In New Zealand, this concern was recently fueled by higher-than-expected Q4 CPI inflation that showed some evidence of less discounting in retail sectors and more significant price rises in the construction sector. We expect choppy trading conditions as investors manage the transition away from the low inflation and falling interest rate environment seen in recent years.

We hope that the following Q&A gives you an insight into our thought process.

What are central banks doing right now?

Central banks continue to provide stimulus by buying large amounts of fixed income assets (mostly government bonds) under quantitative easing (QE) programmes to keep interest rates low and yield curves flatter than they otherwise would be. QE was initiated early last year after cutting policy rates close to their effective lower bounds. The Fed, for example, bought more than US$3trn of bonds in 2020 (14% of GDP) and is currently buying $120bn of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities per month (see Figure 1). In New Zealand, the RBNZ has bought $45bn of bonds (15% of GDP) within its $100bn Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) programme and is currently buying $2.6bn of government bonds per month.

But economies have recovered strongly, why is so much monetary stimulus still being provided?

Economic growth has indeed been impressive in recent quarters but the level of economic activity in most countries suggests spare capacity remains and this is keeping inflation below central bank targets. This is most obvious in labour markets, where developed economy unemployment rates are above those consistent with full employment – a specific objective for many central banks, in addition to inflation (see Figure 2). While central banks, like most analysts, have underestimated the strength of the recovery, they are not willing to recalibrate policy settings yet, as they fear that any move to remove stimulus could trigger stress and volatility in markets, undermining much of the progress that has been made.

Money growth has gone moon-bound, surely inflation is a foregone conclusion?

Large QE programmes have indeed resulted in huge increases in money supply but, outside the housing sector, demand for this money remains relatively weak (see Figure 3). The quantity theory of money states that prices are a function of money times its velocity (the rate at which money is exchanged in the economy), divided by real output. While money has increased, the velocity of that money remains low so that prices of goods and services have not changed materially. The velocity of money is likely to pick up as economies continue to recover.

Aren’t central banks forward looking?

Central banks seem much less forward looking these days. After a decade of missing inflation targets to the downside, many central banks have adopted an average inflation targeting approach since COVID; the US Federal Reserve most formally (see Figure 4). Within this new framework, central banks are placing much greater emphasis on actual outcomes rather than forecast outcomes, i.e. they want to see inflation above 2% and full employment for several quarters before contemplating less accommodative policy settings. Most economists do not forecast these conditions to be met in the next 2-3 years.

What are financial markets saying about inflation?

Markets are becoming more aware of inflation risks. This is due not only to the surprisingly strong economic recovery but also the perceived risk that the approach of central banks may prove to be too slow if inflation does accelerate. Corporates are regularly beating revenue expectations and, in some sectors, noting pricing pressures. Breakeven inflation rates (the difference between nominal bond yields and those of inflation-linked/protected securities) have risen sharply. 10-year inflation breakeven rates are above 2% in the US, close to 2% in Australia and around 1.4% in NZ (see Figure 5). Strong performance in real assets, e.g. property, also speaks to growing concerns about inflation risks.

Do surveys concur?

The evidence is mixed (see Figure 6). The US Philadelphia Fed’s survey of professional forecasters shows their expectations of 10-year ahead US inflation increased slightly at the end of 2020 but remains below 2%. Similarly, the RBNZ’s survey showed 2-year ahead expectations are 1.6%, versus 1.2% in the June 2020 quarter. In contrast, the US ISM survey of manufacturing firms shows prices paid for inputs are increasing – perhaps reflecting supply chain disruptions that some economists assume will be transitory.

How should I think about inflation?

Inflation will mean different things to different people. Some people are mostly concerned about their weekly grocery bills, others about the increasing costs of healthcare and housing. Rapidly increasing inflation impacts the efficiency of an economy; and is more often associated with higher interest rates, lower investment and lower employment.

In a technical sense, most central banks and economists work within a New Keynesian Phillips Curve framework[1] where inflation is a function of the output gap (ie, the level of economic output versus potential, a measure of capacity pressure), historical realised inflation to capture inflation inertia and inflation expectations. For open economies, supply-side variables are often added including changes in oil prices, changes in world manufactured export prices and changes in the nominal effective exchange rate.

What is the risk and how might markets respond?

The most serious risk to asset markets generally is materially higher and persistent inflation. This could happen if spare economic capacity is being overestimated or is reduced more quickly than anticipated. It is likely, for example, that potential GDP growth in New Zealand has slowed due to border closure and the drop in immigration – reducing the growth rate in labour supply.

This unexpected inflation pressure could be exacerbated if COVID-related supply disruptions also persist. The market reaction to this will be determined by whether central banks choose option a) or b):

a) If central banks remain “behind the curve” and leave policy settings unchanged, bond yields are likely to rise substantially (reducing the value of these assets) as they price higher future inflation and economic growth. Inflation-protected securities are likely to benefit.

Equity markets may initially be encouraged by the continuation of central bank support, however at some point equity markets may also react negatively to higher inflation, higher bond yields and the risk of a more sudden rise in interest rates. Historically, inflation averaging between 1-4% has been a better zone for equity market performance.

b) If, instead, central banks show concern about the higher inflation, markets are likely to bring forward expectations of rate hikes and a cessation of QE. Bond yields will likely rise, but by a smaller amount, and inflation-protected securities will not benefit to the same degree.

Equity markets may experience a mixed performance in this scenario with the prospect of cyclicals outperforming utilities, property, and long-dated growth stocks. Given current elevated equity valuations a more prolonged rise in inflation could have a more negative implication for both fixed interest and equity markets.

Sources: Bloomberg, Reserve Bank of New Zealand, US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, Reserve Bank of Australia.

[1] New Zealander William (Bill) Phillips formalised the relationship between inflation and capacity pressure in the 1950’s by documenting (by hand!) the negative statistical relationship observed between UK wage inflation and unemployment. The “Phillips Curve” was quickly adopted by Keynesian economists that believed monetary and fiscal policy can help stabilise economic output over the business cycle, i.e. economic output does not always equal the potential amount of output. This original specification, however, fell victim to critique by the famous monetarist, Milton Friedman, who argued that any efforts to increase output beyond its “natural” level would be constrained by rising real wages as workers adjusted their inflation expectations. The “New Keynesian” response was to incorporate rational expectations (an inflation expectation term) and allow a role for monetary policy by assuming, based on microeconomic justification (menu costs, for example), that prices are sticky.

IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER

Harbour Asset Management Limited is the issuer and manager of the Harbour Investment Funds. Investors must receive and should read carefully the Product Disclosure Statement, available at www.harbourasset.co.nz. We are required to publish quarterly Fund updates showing returns and total fees during the previous year, also available at www.harbourasset.co.nz. Harbour Asset Management Limited also manages wholesale unit trusts. To invest as a Wholesale Investor, investors must fit the criteria as set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013. This publication is provided in good faith for general information purposes only. Information has been prepared from sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of publication, but this is not guaranteed. Information, analysis or views contained herein reflect a judgement at the date of publication and are subject to change without notice. This is not intended to constitute advice to any person. To the extent that any such information, analysis, opinions or views constitutes advice, it does not consider any person’s particular financial situation or goals and, accordingly, does not constitute personalised advice under the Financial Advisers Act 2008. This does not constitute advice of a legal, accounting, tax or other nature to any persons. You should consult your tax adviser in order to understand the impact of investment decisions on your tax position. The price, value and income derived from investments may fluctuate and investors may get back less than originally invested. Where an investment is denominated in a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may have an adverse effect on the value, price or income of the investment. Actual performance will be affected by fund charges as well as the timing of an investor’s cash flows into or out of the Fund. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance. Neither Harbour Asset Management Limited nor any other person guarantees repayment of any capital or any returns on capital invested in the investments. To the maximum extent permitted by law, no liability or responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage, direct or consequential, arising from or in connection with this or its contents.