A piece of the pie: New Zealand’s largest asset class (probably) isn’t what you think

Article written by Dave Tyrer, Chief Operating Officer from Squirrel – 23rd April 2023

People pretty much have four main options when it comes to investing their money: cash, property, equities, and bonds or debt.

Globally, it’s the latter – debt markets – which are the largest and deepest. And, of course, debt comes in a variety of flavours, all backed by different types of security.

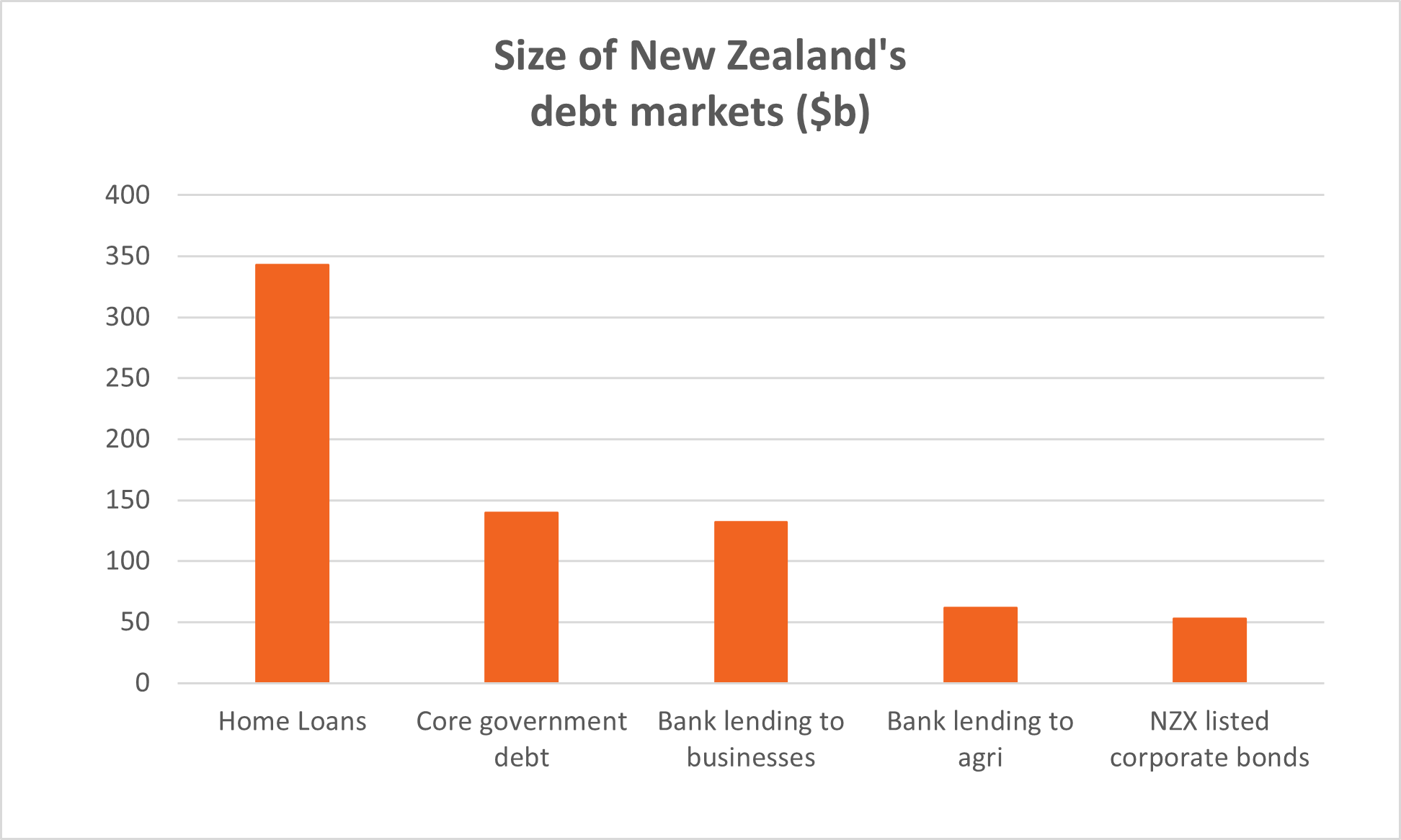

In New Zealand, there’s one part of the debt market that sticks out like the proverbial: residential housing debt.

Kiwi economist and journalist Bernard Hickey has gone so far as to describe NZ’s economy as “a housing market with bits tacked on” the edges. And for good reason, as you can see in the graph below.

New Zealand’s residential housing debt (a.k.a. mortgages) is larger than core Government debt AND bank lending to businesses, combined.

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand statistics and NZX statistics

Breaking residential housing debt down into smaller segments…

- Investment properties account for about $100 billion.

- Owner-occupied homes account for about $244 billion – with a nominal amount attributable to small business owners, leveraging their homes for capital.

In other words, debt on owner-occupied homes alone is roughly $100 billion more than core Government debt. Phew.

So, who funds it all?

Our main banks take the lion’s share.

Roughly 93% of the market goes to the Big Five, the other banks make up the bulk of the rest, and about 1.5% is funded by non-bank lenders.

The RBNZ keeps extremely close tabs on how things are tracking with residential housing debt, including surveying home loan lenders each month, because they know problems here would create major financial instability for the NZ economy. Note, that’s ‘would, not ‘might’.

What are the risks around residential property debt?

When it comes to mortgages, credit loss is essentially a function of two things: the probability of borrower default – usually as a result of changes in income – and changes in property value.

For a lender to incur a loss once a mortgage borrower has defaulted, the loan amount (including any accrued interest and costs) must be higher than what can be recovered by selling the property.

So, if, for example, a loan was equal to 80% of the property’s value, house prices would need to fall by at least 15% before a loss was incurred (that’s with the cost of a mortgagee sale factored in as well).

As a more extreme example… if house prices were to fall 35% on a loan book with an average loan-to-value ratio of 75%, that would mean a 10% loss on property value. And if borrower defaults increased to 3.00%, then the expected overall loss rate would be 0.30% (10% x 3.00%).

For a bank, that would represent around 20% of its net interest margin – or the difference between interest received from borrowers, and interest paid to savers (and the main driver of bank profit). So it would be a weak profit year, but certainly not catastrophic for the bank.

What measures are in place to try and mitigate these risks, and keep our residential housing debt market financially stable?

The RBNZ has implemented a whole raft of regulations and ratios that dictate the way banks can operate (and also help to keep other lenders in check) to help prevent excessive risk-taking.

One example is Loan to Value Ratio (LVR) restrictions, introduced after the GFC, which make it hard for banks to lend over 80% of a homes’ value.

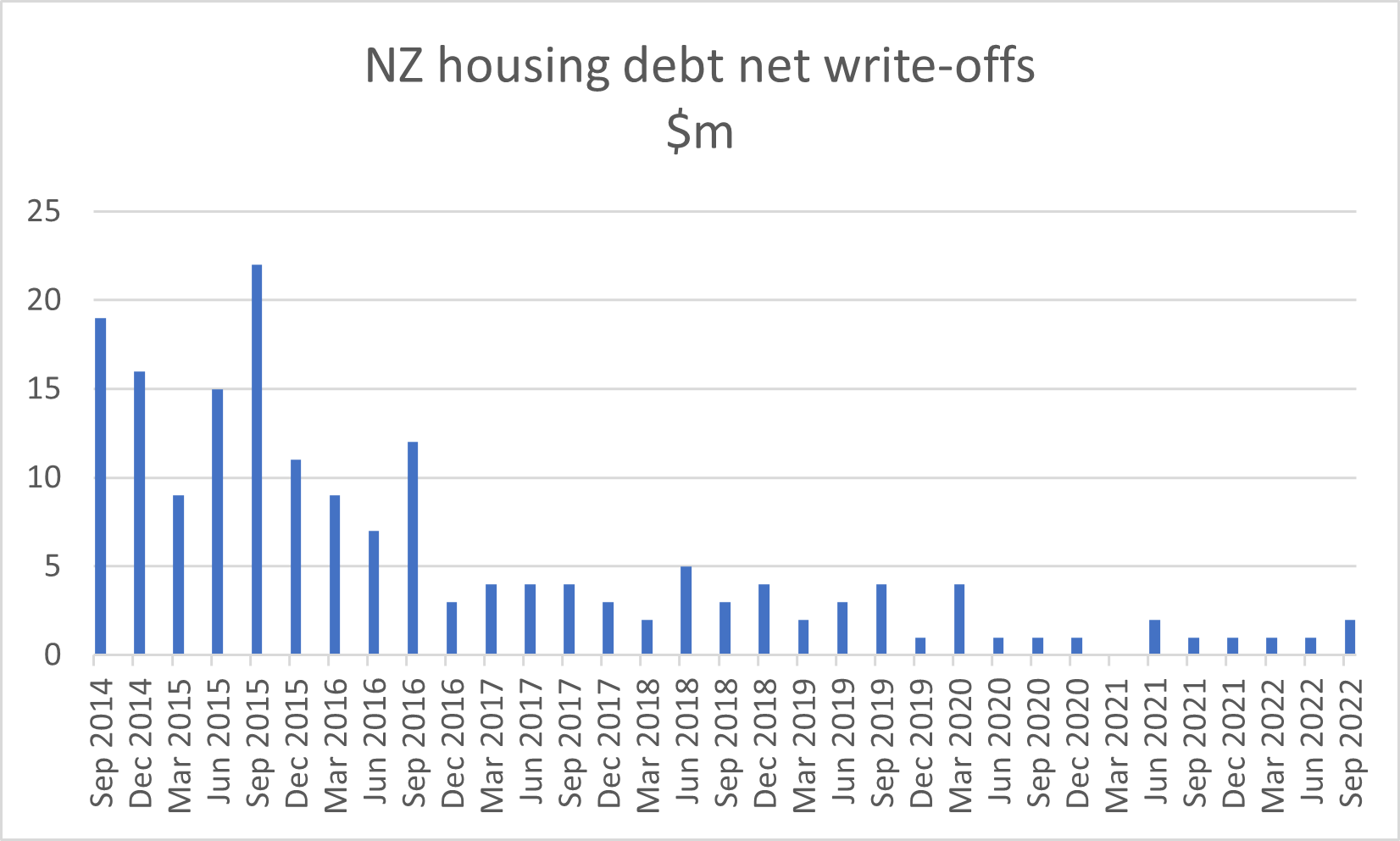

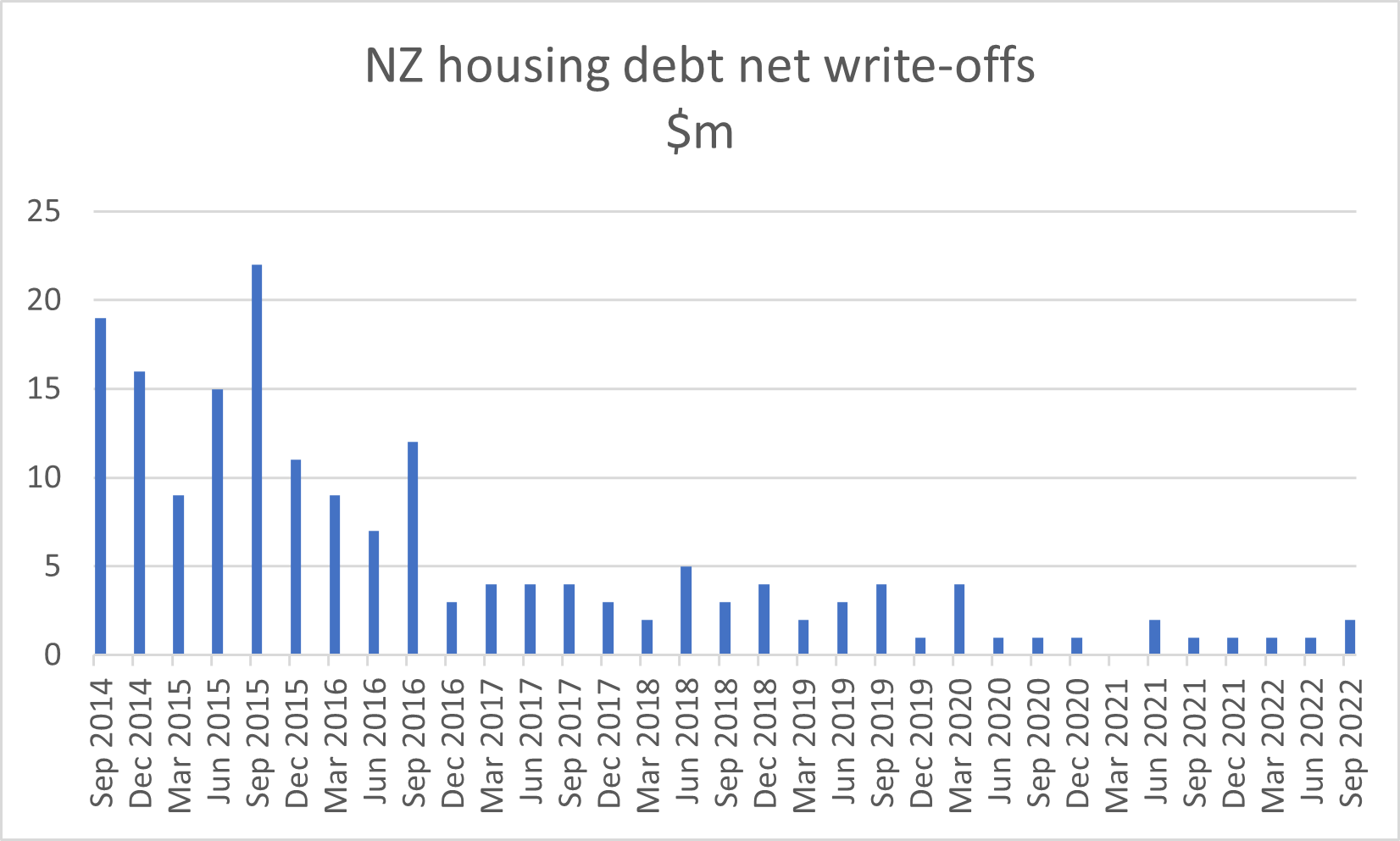

The good news is these measures are pretty effective at doing what they’re designed to do. The graph below, using RBNZ data, shows losses sustained by NZ’s 80+ home loan providers since September 2014, on a net quarterly basis.

(Unfortunately, it doesn’t go back to the early 1990s, or fully cover the GFC.)

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand statistics

Bear in mind that NZ house prices have (generally speaking) been a one-way bet for decades. So, if a borrower did get into trouble, the banks – as first-mortgage holder – could pretty easily sell the property and recover the value of the loan.

But still, in that March 2021 quarter, mortgage lenders didn’t lose a cent – or the amount was so small it was buried in the rounding!

Even looking at some of the bigger numbers – when you consider the size of residential housing debt overall, and the revenue it generates for lenders, those losses pale into nothing.

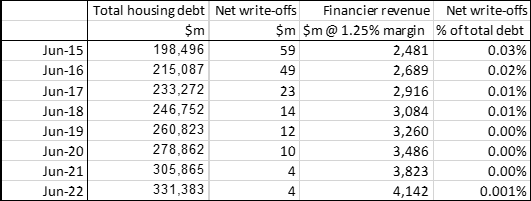

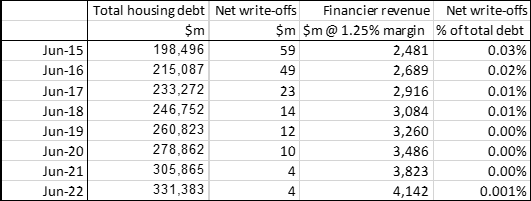

Let’s use the figures for the year to June 2022, in the table below, as an example.

Financiers had collectively lent $331 billion on houses – which generated approximately $4.1 billion in revenue for them that year, while writing off just $4 million. As a percentage of the total portfolio, that’s about a thousandth of a percent!

Is what’s happening in the housing market right now cause for concern?

Looking at the next couple of years, there’s some concern as to whether the historically low levels of losses we’ve had in New Zealand can be sustained.

If we look at countries with a housing market similar to New Zealand’s, the highest loss rate we’ve seen in the last 50 years was in Ireland during the GFC – when, in 2009, write-offs peaked at around 5% of the total housing debt market (or €1 in every €20).

But that came after a period where house prices in Ireland had risen about 50%, and financiers were happily lending at 100% LVR (and over!) in some cases.

To put this in context, if New Zealand’s credit losses hit 5% during any given year, lenders would have to write off about $16 billion against revenue of roughly $4 billion – eating $12 billion of capital in that year.

So, yes – if things go badly wrong, it can cause a lot of pain – but 5% is still a long way from that 0.001% in credit losses New Zealand experienced during the year to June 2022.

While risk does grow as house prices fall, LVR restrictions (with the vast majority of financiers lending at 80% or less of a house’s value) help to minimise that risk, and mean if losses do eventuate they’ll be small.

And remember that for owner-occupiers, their mortgage payment is the single most important payment they make each month. Even if house prices have fallen, people will always make their mortgage payments if they can – so unemployment is perhaps the most important statistic of all to keep an eye on here.

Is residential housing debt a good, safe investment?

No one can predict the future, of course, but investing in housing debt tends to be a ‘steady as she goes’ type investment. While returns may not hit the highs of equities, they’re also unlikely to hit the lows – and overall, the chances of principal losses are pretty minimal.

Key to this is the credit policies used by financiers to mitigate risk – specifically credit risk/losses. Looking at the evidence, lenders (supported by the regulators) are doing a pretty good job of keeping risk under control.

As we’ve already touched on, our financiers and regulators work hard to ensure we never get anywhere near those 5% loss levels. The RBNZ regularly stress tests the banks’ financial position as part of its Financial Stability Report – and most recent tests show they could survive a 40% drop in houses prices, coupled with relatively high unemployment rates.

How do you invest into that huge pile of debt?

Investing into residential housing debt traditionally hasn’t been a readily available option for Kiwi retail investors – because the banks have done such a stellar job of locking up the market. The main ways you can invest, include:

- Taking out a term investment with a bank, or other financiers, with exposure to the housing market.

- Investing in managed funds that focus on the residential debt market.

- Betting on the financiers themselves by buying shares in a bank or non-bank lender

- Trying to get hold of some bank bonds

The returns from each type of investment will vary significantly, so it pays to read up on which might be right for you.

Make sure you also understand the difference between investing in loans on existing houses vs. loans on housing developments. Large developments carry a risk profile quite a bit higher than loans on existing houses.

At Squirrel, we offer investors the chance to invest directly into housing related debt via the Squirrel Monthly Income Fund (available on InvestNow), and by way of Term Investments through Squirrel directly. Check out the Squirrel website to learn more.

A piece of the pie: New Zealand’s largest asset class (probably) isn’t what you think

Article written by Dave Tyrer, Chief Operating Officer from Squirrel – 23rd April 2023

People pretty much have four main options when it comes to investing their money: cash, property, equities, and bonds or debt.

Globally, it’s the latter – debt markets – which are the largest and deepest. And, of course, debt comes in a variety of flavours, all backed by different types of security.

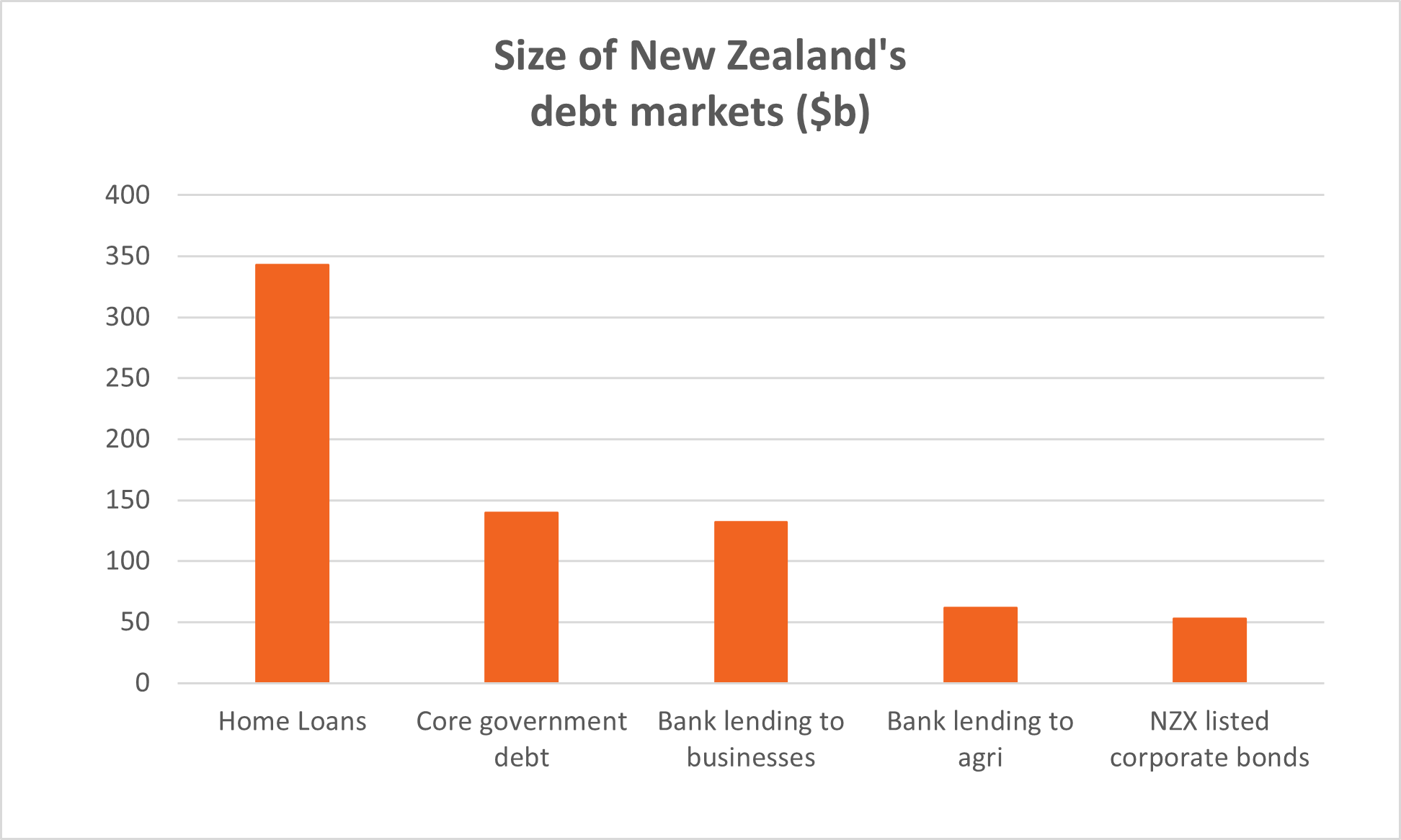

In New Zealand, there’s one part of the debt market that sticks out like the proverbial: residential housing debt.

Kiwi economist and journalist Bernard Hickey has gone so far as to describe NZ’s economy as “a housing market with bits tacked on” the edges. And for good reason, as you can see in the graph below.

New Zealand’s residential housing debt (a.k.a. mortgages) is larger than core Government debt AND bank lending to businesses, combined.

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand statistics and NZX statistics

Breaking residential housing debt down into smaller segments…

- Investment properties account for about $100 billion.

- Owner-occupied homes account for about $244 billion – with a nominal amount attributable to small business owners, leveraging their homes for capital.

In other words, debt on owner-occupied homes alone is roughly $100 billion more than core Government debt. Phew.

So, who funds it all?

Our main banks take the lion’s share.

Roughly 93% of the market goes to the Big Five, the other banks make up the bulk of the rest, and about 1.5% is funded by non-bank lenders.

The RBNZ keeps extremely close tabs on how things are tracking with residential housing debt, including surveying home loan lenders each month, because they know problems here would create major financial instability for the NZ economy. Note, that’s ‘would, not ‘might’.

What are the risks around residential property debt?

When it comes to mortgages, credit loss is essentially a function of two things: the probability of borrower default – usually as a result of changes in income – and changes in property value.

For a lender to incur a loss once a mortgage borrower has defaulted, the loan amount (including any accrued interest and costs) must be higher than what can be recovered by selling the property.

So, if, for example, a loan was equal to 80% of the property’s value, house prices would need to fall by at least 15% before a loss was incurred (that’s with the cost of a mortgagee sale factored in as well).

As a more extreme example… if house prices were to fall 35% on a loan book with an average loan-to-value ratio of 75%, that would mean a 10% loss on property value. And if borrower defaults increased to 3.00%, then the expected overall loss rate would be 0.30% (10% x 3.00%).

For a bank, that would represent around 20% of its net interest margin – or the difference between interest received from borrowers, and interest paid to savers (and the main driver of bank profit). So it would be a weak profit year, but certainly not catastrophic for the bank.

What measures are in place to try and mitigate these risks, and keep our residential housing debt market financially stable?

The RBNZ has implemented a whole raft of regulations and ratios that dictate the way banks can operate (and also help to keep other lenders in check) to help prevent excessive risk-taking.

One example is Loan to Value Ratio (LVR) restrictions, introduced after the GFC, which make it hard for banks to lend over 80% of a homes’ value.

The good news is these measures are pretty effective at doing what they’re designed to do. The graph below, using RBNZ data, shows losses sustained by NZ’s 80+ home loan providers since September 2014, on a net quarterly basis.

(Unfortunately, it doesn’t go back to the early 1990s, or fully cover the GFC.)

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand statistics

Bear in mind that NZ house prices have (generally speaking) been a one-way bet for decades. So, if a borrower did get into trouble, the banks – as first-mortgage holder – could pretty easily sell the property and recover the value of the loan.

But still, in that March 2021 quarter, mortgage lenders didn’t lose a cent – or the amount was so small it was buried in the rounding!

Even looking at some of the bigger numbers – when you consider the size of residential housing debt overall, and the revenue it generates for lenders, those losses pale into nothing.

Let’s use the figures for the year to June 2022, in the table below, as an example.

Financiers had collectively lent $331 billion on houses – which generated approximately $4.1 billion in revenue for them that year, while writing off just $4 million. As a percentage of the total portfolio, that’s about a thousandth of a percent!

Is what’s happening in the housing market right now cause for concern?

Looking at the next couple of years, there’s some concern as to whether the historically low levels of losses we’ve had in New Zealand can be sustained.

If we look at countries with a housing market similar to New Zealand’s, the highest loss rate we’ve seen in the last 50 years was in Ireland during the GFC – when, in 2009, write-offs peaked at around 5% of the total housing debt market (or €1 in every €20).

But that came after a period where house prices in Ireland had risen about 50%, and financiers were happily lending at 100% LVR (and over!) in some cases.

To put this in context, if New Zealand’s credit losses hit 5% during any given year, lenders would have to write off about $16 billion against revenue of roughly $4 billion – eating $12 billion of capital in that year.

So, yes – if things go badly wrong, it can cause a lot of pain – but 5% is still a long way from that 0.001% in credit losses New Zealand experienced during the year to June 2022.

While risk does grow as house prices fall, LVR restrictions (with the vast majority of financiers lending at 80% or less of a house’s value) help to minimise that risk, and mean if losses do eventuate they’ll be small.

And remember that for owner-occupiers, their mortgage payment is the single most important payment they make each month. Even if house prices have fallen, people will always make their mortgage payments if they can – so unemployment is perhaps the most important statistic of all to keep an eye on here.

Is residential housing debt a good, safe investment?

No one can predict the future, of course, but investing in housing debt tends to be a ‘steady as she goes’ type investment. While returns may not hit the highs of equities, they’re also unlikely to hit the lows – and overall, the chances of principal losses are pretty minimal.

Key to this is the credit policies used by financiers to mitigate risk – specifically credit risk/losses. Looking at the evidence, lenders (supported by the regulators) are doing a pretty good job of keeping risk under control.

As we’ve already touched on, our financiers and regulators work hard to ensure we never get anywhere near those 5% loss levels. The RBNZ regularly stress tests the banks’ financial position as part of its Financial Stability Report – and most recent tests show they could survive a 40% drop in houses prices, coupled with relatively high unemployment rates.

How do you invest into that huge pile of debt?

Investing into residential housing debt traditionally hasn’t been a readily available option for Kiwi retail investors – because the banks have done such a stellar job of locking up the market. The main ways you can invest, include:

- Taking out a term investment with a bank, or other financiers, with exposure to the housing market.

- Investing in managed funds that focus on the residential debt market.

- Betting on the financiers themselves by buying shares in a bank or non-bank lender

- Trying to get hold of some bank bonds

The returns from each type of investment will vary significantly, so it pays to read up on which might be right for you.

Make sure you also understand the difference between investing in loans on existing houses vs. loans on housing developments. Large developments carry a risk profile quite a bit higher than loans on existing houses.

At Squirrel, we offer investors the chance to invest directly into housing related debt via the Squirrel Monthly Income Fund (available on InvestNow), and by way of Term Investments through Squirrel directly. Check out the Squirrel website to learn more.

Leave A Comment